Here Is an Overview of How an Extra Army of Glial Cells May Have Fueled His Genius

Abstract: This overview explores the relationship between genius and brain structure, particularly through the lens of Albert Einstein’s brain. Research from the 1980s indicated that Einstein had a higher ratio of glial cells to neurons in specific brain regions, suggesting that these support cells could play a crucial role in facilitating complex thinking. Glial cells nourish neurons and enhance their communication, potentially allowing for deeper cognitive functioning. The article encourages readers to consider their own brain’s potential and emphasizes that while Einstein’s brain offers intriguing insights, it is essential to approach these findings with caution and acknowledge the shared human experience of intellectual struggle and insight.

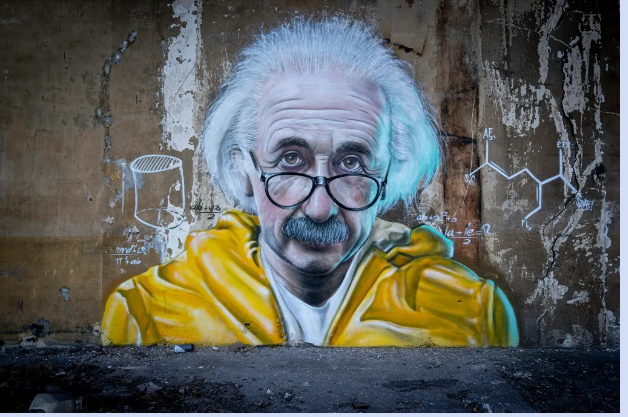

There are moments in life when you pause and think: “What if I could tap into my brain’s full potential?” I remember sitting in my pharmacy lab late one night, surrounded by molecular textbooks, wondering if top thinkers like Albert Einstein had a brain wired differently.

That wonder pulled me in because as a pharmacist and lifelong learner I’ve experienced those moments of insight, of clarity, and also the frustration of hitting mental walls.

That’s why this topic matters, not just for geniuses in labs, but for people like you and me, who believe our brains hold more capacity than we often allow.

When I learned that scientists in the 1980s discovered something unusual about Einstein’s brain, a higher ratio of support cells called glial cells relative to neurons in certain key regions, I felt a surge of hope.

Could it be that deep, sustained thinking moulds our brains in mysterious ways?

Could it mean that even if I (or you) aren’t Nobel-laureates, we can borrow some of the insight, the cellular wisdom behind it? Let’s walk that path together.

The Scientific Insight Simplified

In the mid-1980s, neuroscientist Marian Diamond and her team received four small cortical blocks from Einstein’s preserved brain and compared them with similar sections from 11 other men.

They focused on two regions: Brodmann area 9 (in the prefrontal cortex) and area 39 (in the parietal/association lobule).

In the left area 39, Einstein’s brain showed a lower neuron-to-glial-cell ratio than the controls. In simpler words: for each nerve-cell (neuron), there were more “helper” cells (glial cells) than typical.

Glial cells were once dismissed as mere “brain glue” but we now know they:

- nourish neurons by delivering nutrients/oxygen, dispose of waste, regulate the chemical environment

- influence how well neurons communicate and network with each other

- respond to a brain’s metabolic needs; in simpler metaphor, if a neuron is a star performer on stage, the glial cells are the stage crew, lighting, sound engineers, set-designers who make the performance smooth and possible.

So one way to picture Einstein’s brain is, imagine a concert hall where the main artist (neurons) is given an unusually large backstage team, more tech-crew and support, so the show runs flawlessly and even brilliantly.

His brain didn’t necessarily have more stars, but the stars had an exceptional support system, especially in that left-parietal region that’s tied to integrating visual, spatial, mathematical and language information.

Diamond herself concluded that this might suggest a response of glial cells to greater neuronal metabolic demand in Einstein’s brain, his thinking and conceptual work may have demanded more “maintenance and support” behind the scenes.

This is not a magical explanation of genius. A single significant result (one brain, one region, one ratio) means caution is prudent. The story is suggestive, inspiring, but not definitive.

Why It Should Matter to Us

Here’s where the science becomes human. I’m someone who studies, writes, tries to think deeply about medicine, language and life. Often I’ve felt stuck: my mind buzzing, ideas floating, but not quite forming; the “aha!” moment elusive. Read more….

Thank you for subscribing to my new newsletter on Substack, where I will be sharing my research and personal stories:

I’m a semantic scholar and researcher with over a decade of clinical experience, sharing real-world insights through the art of storytelling. My writing goal is to inform, educate, and inspire my readers.

Leave a Reply